Museums and Exhibitions in New York City and Vicinity

| Home | | Museum Listings | | Theater |

LONEY ON THE ROAD

By Glenn Loney

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

[01] Summer Souvenirs—Gardens & Palaces

[02] Wörlitzer Park—Labyrinth & Grotto

[03] DDR Kraftwerke Vockerode

[04] Königstein/Bastei/Pillnitz

[05] Quedlinburg Treasure Returned

[06] 1200 Years of Salzburg Archbishops

[07] Austria’s Mauthausen Death Camp

[08] Graf Zeppelin’s Museum

[09] 250 Years of Bayreuth Opera-house

[10] Taking a Bath in Baden-Baden

[11] Secrets of Rosslyn Chapel

related article: Expo 98 in Lisbon

You can use your browser's "find" function to skip to articles on any of these topics instead of scrolling down. Click the "FIND" button or drop down the "EDIT" menu and choose "FIND."

Copyright © 1998 Glenn Loney. Illustration by Sam Norkin.

Souvenirs of a European Summer

| |

| Neo-Classical Colonnade and Statues in Potsdam Park. copyright © Glenn Loney/The Everett Collection | |

In Eastern Europe, something similar has been happening in ancient cities and towns. After the ravages of World War II and subsequent structural and decorative neglect under Communism, important architectural monuments are being reconstructed.

And elegant palaces, handsome villas, and noble churches—as well as blocks of impressive houses and apartments—are also being restored, inside and out. This work has been going on as far to the east as St. Petersburg and Moscow, where once shabby palaces of Russian nobility glitter again in their former glory.

This enthusiastic revival of the public and private architecture of vanished Ancien Régimes is not merely cosmetic. True, it has proven an immediate lure for tourists.

But with state-of-the-art Sanierung , the buildings are also made as modernly functional, safe, and attractive as possible. Without unduly compromising their historic characters.

In the former East Germany, this work has been aggressively pursued. What wartime bombing could not destroy, decay, fire, water, misuse and Communist make-overs further damaged.

Now, in Leipzig, Dresden, and Berlin—in the midst of frenzies of Post-Modernist office and apartment construction—the Past is being reborn. But farther east, in cities such as Görlitz and Bautzen, entire streets and neighborhoods are also being reconstructed or renovated.

The effect is rather like that Colonial Williamsburg had on the public when it first opened. Everything looks too new.

A venerable 14th century City-Gate and Clock-Tower, an elaborate Renaissance Palace, a lovely Baroque Church, a handsome row of 19th century Mansions: all now look the same age.

As though they had just been given the last coat of paint yesterday. And Walt Disney’s Imagineers had silently stolen away during the night, leaving the miraculously Preserved Historic Past instantly in place.

But these reconstructions are fortunately not historic variations on EuroDisney. They have their foundations solidly in a real past. And they are all well worth a visit next summer.

Also worth tourist-time are the many Outdoor Architectural Museums. In these, real buildings from past periods have been brought together in attractively landscaped parks to give both travelers and natives a more concrete idea of how farmers, shop-keepers, crafts-people, day-laborers, and aristocrats once lived and worked.

Stockholm has its Skansen ; Danish Aarhus, its Gamla By . There’s even a fascinating Open-Air Museum outside Riga, in Latvia. And another in rural Bulgaria. Such Architecture and Life-Styles Parks are to be found all over Europe.

In Bulgaria, in fact, there are real Roman and Greek ruins poking up out of farmland and in the midst of major cities like Varna and Sofia. Roman theatres and stadia are also to be found in Hungary, Switzerland, France, Germany, and even in England—in St. Albans.

With the rebirth of interest in—and knowledge about—the civilizations of Ancient Greece and Rome in the Renaissance, extant classical ruins, monuments, and sculptures became objects of renewed curiosity and admiration. Some of the most notable of these were ingloriously wrenched from their historic sites and dragged off to alien parks, salons, and museums.

But, for those unfortunate petty princelings and ambitious minor dukes in Central Europe who did not have any real Roman ruins in their domains, it soon became the rage to construct copies or fantastic variations of Classical Architectural Remains.

And, if they could not obtain a real Greek or Roman statue—or even a fragment of a classic cornice—the next best thing was to have copies made of the famed sculptures. And sprinkle them around lavish parks, modeled on the Gardens of Versailles, though on necessarily smaller scale.

One of the most famous and lovely of these is the extensive park at the Nymphenburg Palace, on the outskirts of Munich. The imposing Palace Tract is flanked by the Royal Stables and Orangeries, and complemented by a facing semi-circle of elegant mansions for court officials and manufacture of Nymphenburg Porcelain.

In the handsome gardens beyond, however, there are the Chinoiserie Pagodenburg , the lovely silver-and-blue rococo Amalienburg , the baroque Badenburg —where the Wittelsbach Monarchs could enjoy special baths, and other classically inspired ruins and monuments.

Even in the heart of Munich, behind the Royal Residenz , there are some 18th century architectural curiosities, such as a towering Chinese Pagoda and a soaring Greek Monopteros, with fluted columns. These stand, however, in an Englisch Garten , laid out by the ingenious American inventor-designer, Benjamin Thompson, Baron Rumford.

The symmetrical ordering of Nature—as presented at Versailles and in its many garden-imitations in minor 17th and 18th century courts in Central Europe—was being replaced, or enhanced, by the creation of “natural,” free-flowing English Gardens.

A notable example is the Park at Schloss Branitz . It’s not exactly Windsor Great Park, but it is certainly more natural than the rigidly ordered flower-beds and hedges of the Baroque Era.

One of the palaces of Prince Puckler—whose name survives in Germany on that favorite ice-cream dessert, Fürst-Puckler-Eis —Branitz preserves both old and new ideas in gardening. In the park, there is a huge leafy green elephant, shaped from a bush long ago tormented into this shape.

There are also not one, but two, looming pyramids. Inside one of them—sited in the midst of the large lake in the heart of the park—repose the mortal remains of Prince Puckler.

In his time, he was a great traveler, and one of Germany’s first travel-writers, so he knew a thing or two about pyramids.

But in a time of developing interest in the Secrets of Masonry and Esoteric Arts, Prince Puckler was also fascinated by the Mysteries of the Pyramid—as both form and structure.

A smaller stepped-pyramid at the side of the lake has a curious iron-fence at its summit—with a motto suggesting this as the first stepping-stone into the Hereafter.

Much farther to the north and west, at Schloss Rheinsberg —which has its share of classical ruins and monuments—a Prussian Prince is also buried in a pyramid!

Frederick the Great’s Palace and Gardens at Sans Souci , in Potsdam, don’t attempt to recreate Versailles—much as this amazing monarch admired things French. But they do boast classical ruins and follies on a monumental scale.

One of the most charming of these palace-and-garden complexes is at Schloss Schwetzingen . This was in effect a hunting-palace of the Palatine Wittelsbachs, near their ruling-seat of Mannheim.

Not only does this palace boast French formal gardens and some English landscaping, but it also has one of the few surviving 18th century court-theatres in Germany. The great rear doors of the stage can still be opened to extend the garden perspective of the stage-scenery deep into the actual park.

And it also has a ruined Roman Aqueduct, an old windmill, temples, grottoes, shrines, and even a rococo Turkish Mosque. This is now used for worship by the local Muslim Community.

When I came to teach in Europe in 1956, Schloss Schwetzingen was my first experience of such parks with their Ancient Ruins, Classical Statuary, Great Fountains, and Gilded Follies. I thought it a wonder then. And I still do.

Even after the experience of Versailles, soon after, when I was teaching in France. Today, if I am passing through Heidelberg or Mannheim, a detour to Schwetzingen is always a Must.

It’s best to do it in early June, for this is the all-too-short season of the Schwetzinger Spargel-Fest . This famed local asparagus is all white. There’s no trace of green in its stems, for it is grown with earth heaped around it, so the sun cannot work its photo-synthetical magic.

The Labyrinth & Grotto in Wörlitzer Park

| |

| Greek Temple Folly in Fake Ruined Masonry Wall in Würlitzer Park. copyright © Glenn Loney/The Everett Collection | |

This wonderful 18th century combination of formal and “English” gardens is primarily a place for recreation and relaxation. You have to nosh in the town which adjoins it. So we brought sandwiches.

Wörlitzer—which became transformed to Wurlitzer after crossing the Atlantic—is about halfway between Lutherstadt Wittenberg and Dessau, of Bauhaus fame. Many of the local houses and shops are made of brick-and-timber—which show the ravages of time and neglect—so there’s even an English feeling about the civic architecture, as well as the Park.

Interestingly, the local ruler was a Child of the Enlightenment. Unlike many other Central European royal or princely court-gardens—which were reserved for the rulers and aristocrats of the court—this magnificent garden was always open to local citizens.

Its vast expanse of trees, glades flowers, lawns, lakes, canals, islands, follies, temples, palaces, and orangeries were always there for noble and commoner alike.

Nor was it any different under the People’s Tyranny of the DDR. I first visited Wörlitzer Park on an extensive tour around East Germany in 1987.

After seeing the sights in Wittenberg, I was bound for Dessau with my friend Victor Homola. Even though it was lightly raining, he suggested we stop off and have a look round the Park.

Aside from the occasional day-trip from West Berlin through the Berlin Wall to visit Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble or the ancient Pergamon Altar, most Westerners had little or no opportunity to see anything of the rest of East Germany.

So I was doubly surprised to find a spacious and historic park and an extensive collection of Architectural Follies which were the match of any I’d seen on the other side of the Wall.

Soon, however, it was raining too hard to stroll around. And the photos I did take looked like scenes under water.

When Victor proposed this past summer that we return—with his wife Gabi and daughter Kira, as well—I was eager to see Wörlitzer Park again.

We visited the remarkable old Gothic Parish Church, with a number of surrounding buildings also in Gothic style. The princely palace was handsome, but not as extensive or lavishly decorated as many in Western Europe.

Scattered around this large garden-estate, baroque pavilions, pillared shrines, Greek altars, lone pillars, neo-classic nude statues, romantic arched bridges, and other beloved 18th century landscape decorations were all enhanced by special siting and plantings.

Several mysterious structures here—adorned with various mystical symbols—wouldn’t have been out of place in an English Park. They were evidently Follies, cast in the style of Tudor Gothic.

The sort of small castles or pavilions to which you might ride out in your stately sedan-chair or princely carriage for afternoon-tea or an hour or two of pastel-sketching.

Just our luck! It started to rain again, as it had a decade ago. But we had seen almost all of the Park, and it was too dark to take more photos.

One Historic Folly we had not yet explored was the famous Labyrinth & Grotto. These are found in many 18th century parks. Grottoes, in fact, were often included in some chambers of Palaces and Residences.

They are often made of rough or volcanic stone, but they can also be faked in plaster on wooden forms. Studded with sea-shells and false-fish—with water-dripping stalactites descending from their ceilings—they make attractive romantic framings for either copies or actual classic statues of such Greco-Roman Gods as Poseidon/Neptune.

Complete with shell-shaped basins and elaborate marble or bronze fountains, they provide cool retreats in hot summers. Some—as at Salzburg’s Schloss Hellbrunn —even have concealed water-jets to douse unsuspecting visitors. Peter the Great also thought this was a great joke.

When the grotto-concept is linked to the labyrinth-idea, the fun can become more complicated. Even dangerous!

In a Renaissance or Baroque Labyrinth—evoking that legendary and fearful one in Crete, where the man-eating Minotaur lay in wait for his next meal—the object is not to get lost in blind passages.

And not to cheat by going out the way you came in! You are supposed to find the proper exit. Just as you enter and exit a maze made of tall hedges—also a fixture in such Baroque Parks.

Victor insisted on exploring the labyrinth, even though the sky was darkening and the rain was more than mist. He and Kira entered at the long end. Gabi and I—eager to get back to the car and our sandwiches—took a short-cut near the end.

This brought us into a dark tunnel which divided. I hit my head on a dead-end wall, mottled with plaster to suggest centuries of calcification.

Obviously, that was the wrong tunnel. The other brought me down an incline to a grotto with a marble statue of a goddess—Diana, I think.

Gabi and I followed a stair that emerged on top of the grotto, in front of a baroque pavilion—now a souvenir-shop.

Kira rushed to us to say that Victor had just fallen off the top of the grotto-roof, where we were standing.

We were an entire floor above the bordering street-level of the park. And there was no railing of any kind at the edges of this roof. And no warning-signs.

Victor had apparently been backing away, the better to take a photo of Kira. She shouted to warn him that he was at the edge. But it was too late.

He fell backwards—and he is a big-framed man—off the slippery roof and down the rain-soaked grotto-stairs.

He had landed on his back at the bottom. He was in shock and great pain. He thought his back was broken, but I could see that he could move his fingers and feet.

There was of course no first-aid kit available nor a direct outside phone. The souvenir-saleslady called those who could call a doctor, but that was the end of her responsibility.

It was Sunday, so it took the doctor a long time to arrive. His first action was not to examine Victor—who was moaning and fearing the worst—but to put Victor’s Medical Insurance Card in a portable electronic credit-card device he carried with him.

That way you are sure to be paid, even if the patient dies. He then examined Victor and decided no vertebrae were broken. Only some ribs.

He called the Klinikum Dessau ambulance for Victor and said goodbye. I was surprised he didn’t wait for the ambulance or accompany Victor to the hospital.

After interminable exams, X-rays, and scans in the Dessau hospital—which had pieces of stale bread and other bits of food on its unsanitary floors—Victor decided he wanted to be moved to Berlin.

Hospital authorities contacted the ambulance of the Dessau Fire Department for the trip. Apparently they needed their own vehicle closer to home.

Kira—just thirteen but very brave—insisted on riding in the ambulance with her father.

Gabi drove the two of us back to Berlin through a fierce rain, pitch-blackness, and endless Autobahn repairs. We were trying to follow the Dessau firemen and their ambulance.

We thought we’d lost them, but, when we reached Berlin, they had not yet arrived at the Klinkum Rudolf Virchow . We both had visions of some terrible accident on their way to Berlin.

Two hours later, the Klinik called. They had just arrived!

The Fire Department ambulance had no maps that would show the fire-laddies how to reach Berlin. Or how to enter and exit its Perimeter Ring-Road at the right points.

Victor was in no condition to guide them. But, despite six ribs broken—one of them in two or three places—he was released from the hospital for home-recovery after only a few days.

So, if you think Socialized Medicine works wonders in Europe, think again! It does seem to cover a lot more than Blue Cross, HIP, and other American insurances and services. But the services and coverages, at least in Dessau, could be greatly improved.

Not to mention some improvements at Wörlitzer Park! Like guard-rails and warning-signs. Like first-aid kits and blankets, outside phone-lines or police-phones, and park-employees trained to assist in medical emergencies.

Despite our collective misfortunes that fateful July day, Wörlitzer Park is still worth a visit. But I didn’t get to eat my sandwich until we were back in Berlin.

DDR Kraftwerke Vockerode and Saxon History

| |

| Four Great smokestacks of Disused DDR Vockerode Power-Plant. copyright © Glenn Loney/The Everett Collection | |

This is the vast Kraftwerke Vockerode , a huge electric-power and hot-air heating plant. With tons of brown coal arriving hourly on Elbe barges, it serviced a large area of Saxon-Anhalt during the infamous DDR. Or the East German Democratic Republic.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall—and of the DDR/GDR government soon after that—this major power-source was stripped of its generators and other machines. And left to erode and decay.

But, as it was actually constructed in the 1930s, during the Nazi Era, its super-thick and steel-reinforced walls will still stand firm for many years. Hitler and Reichsminister Prof. Dr. Albert Speer apparently ordered such monumental structures to be designed and built to endure during the entire Thousand Year Reich.

When the Federal German Treuhand —or Trustee—Organization surveyed the factories and public utilities of the former East Germany, it attempted to sell off as many as possible to Free Enterprise entrepreneurs.

Those operations and manufacturies which no one wanted—since they could not be operated at a profit, or at least not an immediate one, without much more investment and modernizing—Treuhand promptly shut down.

This has left many small towns and villages—and their citizens—in the former East Germany without work. This on-going tragedy has happened not only to Vockerode, where the power-plant is located, but also to the inhabitants of the immense steel-plant at Eisenhüttenstadt.

Thousands remain out of work—with no new industrial development anywhere on the horizon. Nor can they sell their homes—who would buy a house or apartment in an area with no employment opportunities?

As joblessness is on the rise in the western parts of Germany as well, migrating to Munich, Frankfurt, or Hamburg is futile. And Arbeitslose from the East are definitely not welcome!

As it was originally designed, the Vockerode Kraftwerke cannot now be effectively or economically modernized to provide the area with electric-power and heating. Other arrangements have already been made.

Nor would it make sense to try to fit some other kind of manufacturing operation into the existing spaces, vast though they are.

Sitting stripped and empty—with only its immense, towering coal-ovens still in place—it seems a possibility as location for a Horror or a Holocaust Film. Or, if it cannot be used to suggest a cinematic Extermination Camp, it could at least serve as an actual asylum for political refugees.

But Germany is gradually closing down such asylum sites and actively trying to discourage more displaced persons from flooding in and burdening its already strained economy.

So the local authorities in Vockerode have decided to use the Power-Plant as a site for museum exhibitions, cultural events, and other kinds of recreation.

It was recently inaugurated with “Mittendrin,” a museum-documentation of the central role of Sachsen-Anhalt in centuries of Central European history.

This might seem laughable pretension to those who know nothing of the history of the Holy Roman Empire and of the area itself.

But Vockerode and Sachsen-Anhalt were—as the exhibition title suggests—right in the middle of it all.

Once this great landscape was under the dominion of the Ottonian Kings. From the roof of the Kraftwerke, you can see the spire of the Wittenberg Church where Martin Luther nailed his famous Theses to the door.

This whole area was once a hotbed of the Protestant Reformation. In the early years of the 20th century, nearby Dessau nurtured a different kind of revolution. It was the home of the famed Bauhaus School—the cradle of Modernism and the International Style.

So there is a great deal of history—political, social, spiritual, and cultural—to put on documentary display. And the actual artifacts range from ancient sculptures, through 19th century steam-traction engines, to 20th century technologies.

Some are on view on one of the vast floors of the Kraftwerk. But most have been isolated by era and put on display inside the hearts of the now dead ovens.

These are claustrophobic spaces, entered by small steel-framed door-ways. Outside, they are clad in scores of thick heating pipes which rise upward.

Any tourist who has ever been inside a Nazi Concentration Camp gas-chamber is apt to have unpleasant sensations. That these rooms may have been used for a different purpose than generating heat to drive turbines. And that someone might suddenly slam the steel door shut and lock it!

Neither lurking fear is justified. But, interesting as the displayed bits and pieces of Saxon History were, I was only to glad to get out of the ovens and back onto the vast main floors.

For those who love to climb—and for those who love exploring old factories and mines—the entrance to the Power-Plant is worth the whole trip to Vockerode.

Outside the great building, there are towering separate coal storage-silos. From the bases of these, coal was shuttled onto two large endless conveyor-belts which gradually raised it up, inside a brick-enclosed inclined passage, to the tops of the ovens.

That is the way visitors have to enter as well. Up the very narrow steps between the two beltways, which are now only endless cradles of metal-rollers for the vanished belts.

If you ever visit Dessau or Wittenberg—both rich in historical associations—a side-trip to Vockerode is definitely worthwhile. Even though Mittendrin may then have been replaced by a new exhibition. Or by a local folk-festival.

The gigantic scale of the plant and its smokestacks is amazing, even without supplementary shows!

[In Wittenberg, you can also see the initial tomb of Sweden’s King Gustavus Adolphus. He was mortally wounded on the battlefield of Lützen just outside the city during the Thirty Years War.

[Later, his remains were disinterred and returned to Stockholm. Where you can now see his Bloody Shirt—and the musket-ball which killed him—in the National Museum!

[His former Wittenberg tomb is in the church at one end of the town-center. At the other is the Luther-Church, where the bodies of both Luther and his strong supporter in the Protestant Reformation, Philip Melanchton, are buried.]

Festung Königstein, Bastei, Schloss Pillnitz

| |

| Baroque Water-Gate & Stairs of Schloss Pillnitz, with Dresden Steamship Cruising by on River Elbe. copyright © Glenn Loney/The Everett Collection | |

It was used for centuries primarily as a military outpost of obvious strategic importance to the Kings of Saxony. Its thick walls, constructed on the almost vertical stone mountain-foundation, still boast quaint guard-turrets and bronze cannon.

Ancient masonry barracks, powder-magazines, a church, a small Residenz, a lovely baroque pavilion high above the Elbe, and a museum are among its attractions.

It also offers magnificent views of the panorama of farmlands and cities for miles around. Across the Elbe, however, is another great mountain, also rising abruptly out of the Elbe Plains.

This is the breath-taking Bastei, a stone bastion—with a commanding view of the Elbe below. Clambering along narrow paths and stone bridges among the many stone pinnacles of its summit, one is reminded of some eroded rock-formations in Bryce Canyon, though these in Saxony are gray granite.

It’s easy to understand how the Saxon Monarchs could control shipping—and customs-duty—on the river below, given this towering site for long-distance surveillance and cannon emplacements.

In the lower rocky ranges of the Bastei—reached by Elbe steamship from Dresden—is the Felsen Bühnen Rathen. This open-air stone-theatre this past summer was offering a Karl May vision of the American Wild West, complete with May’s heroes, Winnetou and Old Shatterhand.

May, who was born not far from here, never saw the American West or an American Indian on native grounds. Nonetheless, his imaginings remain definitive for many Germans, young and old.

In 1987, I saw Carl Maria von Weber’s “Der Freischütz” performed on this very stage. It is still in the summer repertory. Along with Carl Orff’s “Carmina Burana,” Otto Nicolai’s “Merry Wives of Windsor,” and Shakespeare’s “Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

Nearer to Dresden is a wonderful summer palace of the Saxon Kings and Electors. This is Schloss Pillnitz, with a number of handsome palace buildings. Several are being richly restored to baroque elegance.

One of the most impressive features is the Water-Gate and Steps by which royals and nobles arrived from Dresden for visits and parties. There’s even an elaborately carved and gilded Royal Gondola.

And a hundred-year-old magnolia-tree protected by a huge glass pavilion in the extensive formal gardens.

Stolen Quedlinberger Domschatz Returned

| |

| Towers of Quedlinburg’s St. Sevatius Cathedral and Castle. copyright © Glenn Loney/The Everett Collection | |

For many years after the Second World War, they were thought to have been looted by the Russians. Or to have disappeared forever.

They had been securely and safely hidden inside a tunnel in a local hillside throughout the war. They suddenly disappeared only after American troops occupied this ancient East German city.

Their historic and symbolic value far exceeded any sum that could be estimated for the worth of their jewels, gold, and workmanship.

Quedlinburg was the seat of the first real German King, Heinrich the Lion. A marvelously bejeweled book of gospels from this era was among the missing treasures.

Immediately after World War II, many cities and towns in West and East Germany rapidly realized that priceless religious and secular treasures and artworks had vanished.

Some had been violently wrenched from church-altars. Others had been lifted from museum walls. Still others were stolen from private collections and homes.

Some were even bartered to Allied Troops for butter, sugar, chocolate, or cigarettes!

The Soviet Occupation Troops—aside from any private personal acquisitions—were under orders to see that major artworks and collections be seized and sent to the Soviet Union.

Thus the Golden Treasures of Priam’s Troy were dispatched to the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. Where they remained in secret for more than 40 years, only recently having been put on public display.

Nor do the Russians have any intention of returning them to the Berlin Museums from which they were taken.

At a major New York conference on War Booty in 1995, Irena Antonova—their curator for all those secretive years at the Pushkin—made it clear that anyone who wants to see Priam’s Gold can come to Moscow to do so. She told me so then, inviting me to the opening of the recent exhibition.

This fascinating and very informative conference was sponsored by the Bard College Center for Studies in the Decorative Arts and its director, Susan Weber Soros. It was officially titled “The Spoils of War—World War II & Its Aftermath.”

Before the demise of the Soviet Union, its official position on War Booty was that the Germans had stolen so many irreplaceable artworks—not to mention having destroyed historic architecture, monuments, and entire museums—that the Soviets had the Right of Plunder. To replace what they had lost.

Today, the Russians still maintain that position.

But, because the Allies—notably some American and British officers assigned to the task—were so thorough in cataloguing and returning all artworks stolen or coerced from museums and private owners, the Germans have very little left to swap with the Russians.

Some German museum experts privately blame some of the American officers for having been “over-zealous” in repatriating major works from the art secured in Austrian Salt-Mines. As well as items from Hitler’s and Goering’s private collections, found in railway freight-wagons in the Berteschgaden area.

America and Britain were rigorous in not officially seizing any artworks as War Booty. Nonetheless, that did not prevent some soldiers from “liberating” rare books, illuminated manuscripts, gold and silver religious and secular vessels, statues, and priceless paintings.

Some rare panels painted by Albrecht Dürer came to light in Brooklyn not so long ago. They were returned to their rightful site.

But what had become of the Treasures of Quedlinburg Cathedral remained a mystery. Had they been lost forever?

If they still existed, why hadn’t one or more of them surfaced somewhere? Any element in the treasures would be worth a great deal of money.

Finally, one of the bejeweled Quedlinburg Gospels was offered for sale—but its real provenance and historic significance was not noted.

Gradually, it came to light that the sacred treasures had been stolen from their hillside hiding-place by an American Army Lieutenant, Joe Bob Meador—who had ironically been ordered to prevent thefts.

He sent them to his home-town of Whitewater, Texas, by regular APO mail. After he was discharged from the Army—for another theft—he returned home to take charge of the family hardware store.

Joe Bob Meador told the very few friends and family-members to whom he showed these beautiful objects that they were given him by grateful Germans. Apparently, none of these West Texans questioned that explanation.

Later, he moved to Dallas, where some smaller treasures must either have been given to—or stolen by—men he brought home for fun-and-games.

But he made no attempt to sell any of them during his lifetime. Only after they had passed to his sister and brother, did anything come on the international art-market.

The story of their eventual return to Quedlinburg Cathedral is a fascinating one. There is even a book about it: “Quedlinburg To Texas and Back: The Black Market in Stolen Art.”

The story was also outlined at the Bard War Booty Conference, featuring William Honan, of the New York Times, Thomas Korte, and Thomas Kline. All of whom were involved in the process of the return of the Quedlinburg Treasures.

A financial settlement was apparently made with Meador’s heirs, to facilitate the treasures’ return to Germany.

But this was only the beginning of their difficulties, for they had knowingly connived at the concealment of extremely valuable foreign artworks. Priceless objects which had never been declared for customs, among other delinquencies.

In 1993, Prof. Dr. Rita Süssmuth, President of the Federal German Parliament, saluted the official return of the Quedlinburg Domschatz to St. Servatius.

This past year, the cathedral-church’s retired pastor, the Rev. Friedemann Gosslau, has published an interesting book about the whole affair. It’s called “Verloren, gefunden, heimgeholt.”

Or “Lost, Found, Brought Back Home.” He even details conversations with some of Joe Bob Meador’s gay men-friends in Dallas who had actually seen some of the treasures.

This slim book is also of interest for its all-too-brief account of Gestapo Chief Heinrich Himmler’s take-over of the Cathedral. He wanted to celebrate the Thousand Year Reich in 1936—which began in 936 AD with the death and burial in the cathedral-crypt of Heinrich I, the First German King.

Himmler effectually de-sanctified the age-old Christian church, to turn it into a elitist site for Nazi revivals of ancient pagan rituals. He even altered its interior architecture to better facilitate his own Ceremonial Mysteries.

Actually, the cathedral-church and its adjoining castle were for centuries one of Central Europe’s most important women’s monastic foundations. When King Henry I died, his widow Mathilde—also buried in the crypt—transformed these into a Frauenstift.

She was herself in charge for 30 years. In 966 AD, Her grand-daughter Mathilde—the child of Emperor Otto I—was confirmed as the first Abbess before all the Archbishops and Nobility of Germany.

The first Ottonian Emperor also enlarged the Foundation with rich and extensive lands and properties. He also guaranteed the monastery Imperial Immunity and Freedom. His successors added to his gifts and to the Domschatz.

The daughters of major monarchs and nobility were educated here. By the year 1207, almost 70 visits of German Kings and Holy Roman Emperors were noted in the monastery record-books.

Thoughtfully, they all brought treasures with them to adorn the cathedral or to enrich the foundation. Its lands and valuables became most impressive.

Catholic worship came to an end with the death of the Foundation’s Patron, Elector George of Saxony. The Abbess Anna II then introduced Martin Luther’s Reformation—and Evangelical Protestant worship continues in the cathedral-church to this day.

In 1802, as Napoleon was sweeping—and reforming—across Europe, the now Protestant monastery was dissolved. Its last Abbess, a Gustavian Swedish princess, returned to Stockholm.

The Foundation Church and Castle became the property of the Prussian State.

Quedlinburg continued to thrive over the years. Even at the end of the 19th century, prosperous merchants were building richly carved wood-and-plaster houses in the style of the many surviving medieval buildings.

World War II did damage to the city. And the poverty and neglect of the DDR regime made much of the historic city deteriorate even more.

Now, with the reunion of the Two Germanys, the city is experiencing a real architectural renaissance. Ancient buildings, as well as Baroque and Jugendstil houses have been handsomely restored.

This past summer, it was teeming with international tourists. And the returned Quedlinburg Domschatz wasn’t the only reason they’d come.

Its shops feature all the Big Brand-Names of Luxury Merchandise. And there’s a wide variety of good restaurants and comfortable hotels now.

1200 Years of Salzburg as an Archbishopric

| |

| Sun Spotlights an Ornamental Urn in the Fantastic Mausoleum of Salzburg Prince-Archbishop Wolf-Dietrich. copyright © Glenn Loney/The Everett Collection | |

Many of them were in fact Fürst-Erzbischofe, Temporal Princes and Spiritual Potentates as well. Today, though the incumbent no longer rules the City and Land of Salzburg, he is still designated as the Primate of All Germany.

This is a title the Salzburg Archbishops have held for many hundreds of years. No Cardinal outside Salzburg, whether Austrian or German, has ever held that Papal Honorific.

At one time in history, the lands and powers of the Salzburg Archbishops extended beyond the borders of modern Austria.

Salzburg stood at a nexus of trade-routes East and West and North and South. It also controlled great deposits of salt—in crystals or saline-solution—which was as good as gold. Even better, when it came to seasoning food!

In the 18th century, the Salzburg Prince-Archbishop even had the power to expel all the native Protestants from his domains. Which he did with gusto.

They all had to sell their farms and livestock, or shops—often for very little—and leave this High Catholic Land forever.

Some emigrated to East Prussia, thanks to the intervention of Frederick the Great. Others sailed to Georgian Savannah—where you can still see their original settlement of Ebeneezer today.

Some of these autocratic Salzburg rulers were not as spiritual as they should have been. The lovely Mirabel Palace is said to have been built for a Cardinal’s Mulatto Mistress.

But the greatest of these Churchmen were builders of impressive churches, seminaries, residences, and fountains. The architectural beauty of Baroque Salzburg is owing to such picturesquely named Archbishops as Paris Lodron, Wolf Dietrich, and Markus Sittikus.

To celebrate this important anniversary, the Cathedral Museum has mounted a major exhibition of “Masterpieces of European Art.” These are drawn not only from the extensive and priceless collections of the Cathedral, but also from major museums.

One of the most macabre objects on display is a wax Death-Mask of Pope Innocent XI. His head is encased in an ermine-lined cowl. This makes him look like a sleeping Santa Claus. But the gold-framed mask is also ringed with a cheery garland of fruits and flowers.

There is a richly illustrated catalogue of this splendid exhibition: “Meisterwerke Europäischer Kunst.” It has been deftly edited by the Cathedral Museum’s Director, Dr. Johann Kronbichler. He and 19 other art-experts have contributed the many individual essays which discuss each artwork—as well as its religious, historical, and creative significance—in detail.

It is well worth having for the photos of the artworks alone, if you are especially interested in religious art, or in the Baroque Era. Even if you don’t read German, it’s a handsome visual reference.

For more information about the catalogue, contact Dr. Kronbichler, Dommuseum zu Salzburg, Kapitelplatz 6, A-5020 Salzburg, Austria.

Mauthausen—Austria’s Biggest Death Camp

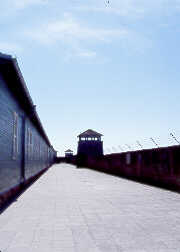

| |

| Guard-Towers and Barracks at Austria’s Mauthausen Death Camp. copyright © Glenn Loney/The Everett Collection | |

If you can stand a brief exposure to Austria’s Nazi Past, an outing to this forbidding fortress will be a sober reminder of the horrors which faced Jews, Socialists, Communists, Liberals, Gypsies, and Homosexuals until the Allies opened this prison in 1945.

And a visit can also be a bitter reminder that the Land of Haydn and Mozart was much later the Birthplace of Hitler. This chief of all Austrian Death Camps has been preserved as a monumental memorial to those who died here.

One of its most painful sites is the “Parachute Jump.” Here, over the edge of the high face of the great rock-quarry, Jews were pushed to their terrible deaths, shattered on the rough rocks below.

In fact, the great stone walls of the vast Death Camp were constructed of stone quarried here. Quarried by prisoners who then were forced to build the super-thick walls which enclosed them and many, many thousands of later victims.

Today, most of the closely crowded wooden barracks are gone. Only one row has been preserved—as at Dachau. This shows how prisoners existed when not employed in torturous slave-labor.

It is paralleled by an even longer row of narrow buildings, constructed for camp functions such as food-service, torture, hanging, gassing, burning, corpse-storage, and dissection of the newly executed.

Small wonder that many of the older visitors who work their way through these corridors—peeking into gas-chambers, staring at the open doors of crematory ovens, and studying the overhead hooks for hangings—have tears in their eyes.

Currently, there are three impressive exhibitions in the row of “administration buildings.” One of these deals with the rise of Austro-Fascism. Adolf Hitler—a native son of Austria, born in Braunau on the River Inn—certainly had his admirers in Austria long before its annexation into Grosses Deutschland, with the Anschluss of 1938.

This display of photos, documents, posters, and texts is titled “1938—NS Rule in Austria.” It will remain in Mauthausen only until December 15. After that, it’s to be hoped that it can be widely toured.

An English-language version should be especially interesting to many who live in North America. Not only does this exhibition document in detail the steps by which the Nazis were able to seize control of the Austrian government—at all levels.

But it also makes the strong point that this did not succeed without strong internal opposition to the Nazis. Right up to the end of World War II, there was a Resistance Movement of native patriots—many of whom gave their lives to bring Nazi domination to an end.

For decades, it has been both painful and embarrassing to Austrians who lived through those hard times—and to younger Austrians as well—that so many English-speaking people still think that Hitler and his armies were warmly welcomed into Austria.

Even the triumphal photos in this exhibit show nothing but jubilation. But there is another quite different Austrian narrative: that of the Resistance.

Unfortunately, its story is little known in the West. If this show is able to tour, it may do much to restore some balance in these two parallel Austrian histories.

It can also serve as a bitter reminder of how easy it is—especially in times of severe economic and social distress—for Fascism to prevail. This is now the Specter that is Haunting Eastern Europe. Neo-Fascism, not a return to failed Communism.

This exhibition has been made possible by the Austrian Ministry of the Interior and the Documentation Archive of the Austrian Resistance.

It is also worth noting that one of the most important national days of observance in modern Austria is the day on which the Allies formally liberated the nation from its Nazi Overlords!

There two other—and even more shattering—permanent exhibits in the administration buildings. One relates to the Concentration Camp itself. And to the scores of sub-camps, all over Austria, administered from Mauthausen.

The other display deals with the horrors experienced by Austrian citizens—both Jews and non-Jews—in the Nazi Death Camps of Ravensbrück, Sachsenhausen, Dachau, Buchenwald, and Auschwitz. And notably with the plight of the Jews sent to the “Model Ghetto” of Theresienstadt, known in Czech as Terezin.

Almost all of these were Slave-Labor Camps, where thousands of men and women were worked, beaten, and starved to death.

Some worked in tunnels, making parts for the V-2 Rockets. Some died in mine-tunnels. Some died building highways for the Nazi Armies. Some expired in the forests, cutting trees.

And not only Jews were enslaved and died, despite the limitations of the Holocaust Narrative.

Orthodox Rabbis may still despise and denounce homosexuals. But they also died horribly—as did their Jewish fellow-prisoners—in Mauthausen, Dachau, Sachsenhausen, and Auschwitz.

They, like the unassimilated Gypsies—the Roma and Sinti—were regarded by the Nazi Master Race as “Asocial Elements.” Even now, the Gypsies still have few advocates in Central and Eastern Europe.

Mauthausen was opened for the business of incarceration, slave-labor, and extermination on August 8, 1938. The Nazis had invaded Austria only that March, so they moved very quickly to impose their Reign of Terror.

Mauthausen was opened by Allied Troops on May 5, 1945. Those prisoners who had survived looked more like skeletons than living human-beings.

Here is what the Memorial & Museum Guide has to say about this:

“From 1938 to 1945, Mauthausen was a name that spread fear and terror. Mauthausen-Gusen was synonymous with death through slave labor in the quarries. More than 195,000 people were imprisoned in Mauthausen and its sub-camps, and more than 105,000 of them—both men and women—were killed there or perished as a result of the torments of camp life. The soil of this vast stronghold is soaked with the blood of thousands of innocent people.

“To remind future generations of what the National Socialist tyranny of Hitler Germany meant for our people and for all mankind, the Austrian Federal Government set up a worthy memorial, a place of warning and commemoration, at the site of the camp.”

On the interior stone walls of Mauthausen, there are many plaques from many lands—honoring both the dead and the survivors. Pope John Paul has placed his memorial among them.

Some of the long tracts which once were filled with barracks are now silent cemeteries inside the high stone walls.

In front of the main-entrance to the camp, the sloping hill which extends downward to the face of the Death Quarry is covered with a profusion of monumental memorials to victims from various lands and ethnic groups.

Individually, most of them are quite striking, even extraordinary. But haphazardly massed as they now are, they lose their intended effect. The hillside is monumentally overwhelmed with Memorial Overkill.

Among the nations represented are West Germany, the DDR, Bulgaria, Belgium, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, the Netherlands, Hungary, Greece, Poland, France, Italy, and Luxembourg.

Historic Mauthausen—from which the dread Death Camp takes its name—is actually a beautiful medieval town sited on a curve of the broad River Danube.

Today, impressive old buildings from the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Baroque Era—some with glorious and colorful stucco decorations—compose a marvelous architectural museum.

As with centuries-old Dachau—the city of Dachau, not the Dachau KZ—the City of Mauthausen did not ordain nor construct the Death Camp. Yet few visitors to either camp want to spend any time in the towns from which the camps took their names.

Mauthausen was chosen as a camp-site primarily because its rolling hills are composed of an excellent granite. This was needed for some of Hitler’s more ambitious architectural construction projects.

The actual camp sits on top of just such a hill, one side of which is an open quarry-face. There are other quarry-sites nearby, unworked today.

The Danube and a local rail-line made it easy to ship cut stone and import new slave-laborers. Still, Mauthausen seems remote, even now, from major centers such as Linz, Salzburg, and Vienna.

It is especially remote for those who feel they must visit this Memorial and Museum, but who are not driving a car.

To reach Dachau Concentration Camp, by contrast, you simply get on one of the frequent local S-Bahn trains at Munich’s Main Railway Station. At the Dachau Station, buses are waiting to take you directly to the Concentration Camp Memorial Site.

And they speedily return you to the station, where the S-Bahn rushes you rapidly back to Munich. Without so much as a glance at Dachau’s Castle and other ancient buildings.

At Mauthausen, on the other hand, you can experience your own personal Death March. If you decide to try to walk the six kilometers uphill to the camp on a hot summer day, the first steps could be your Last Mile.

Just getting to the Mauthausen Railway Station is a real effort. From Salzburg, you take the train to Vienna. But you get off at the tiny town of St. Valentin. And wait for a pokey local train which stops at Mauthausen, among other rural stops.

I made the mistake of going on Sunday, when there are even fewer trains. When I arrived at the Mauthausen Station, there was nothing to indicate that the infamous Death Camp was nearby.

If six kilometers uphill can be called nearby.

Nor was there a bus waiting. Or even a taxi. Some young Americans and Europeans were renting bicycles from the station-master. I never had a bike and did not feel, at 70, that I was ready to learn to ride uphill.

What to do, having come so far?

The station-master called the local taxi for me, but the driver was nowhere to be found. After repeated and unanswered calls, he studied the train-schedule and decided there was time enough for him to shut his office.

So he generously drove me and a young American couple to the gates of Mauthausen KZ.

He gave me the station phone-number so he could come to pick me up when I’d had time enough to experience vicariously all the horrors of that evil place. An infinitely anguished aura engulfs it, even on a sunny day.

In the event, the day was so lovely I decided to walk back downhill. Through wooded pathways, by ripe fields of barley, and into charming hillside lanes, fringed with flower-gardens and chalets. Complete with gardens crowded with plaster casts of merry red-capped dwarfs and Snow Whites.

After the grim recollections of the Death Camp, the vista of the Danube and the handsome old town were a strong and strange contrast. But also worth a visit—all the more because of that incongruity between Past and Present, between Death and Life.

If you are going to the Salzburg Festival—or just touring Austria—Mauthausen is a place you might well want to see. Rent a car and plan to spend an entire day on this excursion into incredible horrors.

Graf Zeppelin’s Lighter-Than-Air Museum

| |

| Monument Inscription to Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin by Friedrichshafen Harbor: “One only has to want to do it and believe in it and it will succeed.” copyright © Glenn Loney/The Everett Collection | |

After the disaster in Lakehurst, New Jersey, these huge airships no longer appeared to be useful in either war or peacetime. In fact, they have never completely disappeared from the world’s airways.

Shakespeare in Central Park is often interrupted by blinking electronic Tommy Hilfiger ads on the sides of a slowly cruising blimp. Soon cargo-container dirigibles will be making their appearance in the skies.

Almost immediately after the bursting of Count Zeppelin’s lighter-than-air dream in Lakehurst, the Zeppelin factory in German Friedrichshafen opened a Zeppelin Museum.

At the end of World War II, the French Occupation Troops took most of its valuable exhibits back to France. Just as they had done with actual Zeppelin airships, after World War I.

At that time, having successfully bombed major cities in England, the Zeppelins promised to be important factors in future wars. But the development of fighter-planes and long-range bombers, in the years leading up to the Second World War, ended that dream as well.

Today, on the shores of Lake Constance, in Southwestern Germany, a new Zeppelin Museum has recently opened. The historic artifacts taken by the French have largely been returned.

The museum is housed in the restored Art Deco Harbor Railway Station. It is big, but not large enough to contain an entire Zeppelin.

So a section of the old Hindenburg has been newly reconstructed in one of its great halls. Its design, technology, and interior-decoration were state-of-the-art in 1937.

This huge section shows how the outer skin was laced to the aluminum skeleton. And it also gives visitors an intimate look at the way the Hindenburg’s celebrity passengers slept, showered, ate, and amused themselves on the silent, gliding journey across the Atlantic.

For lovers of Art Deco, the gleaming chrome chairs and Bakelite surfaces will evoke the high point of Moderne in the mid-1930s.

But, compared with the luxury of such great ships as the doomed Titanic, the all-too-brief-lived Normandie, and the venerable Queen Mary, accommodations on the Hindenburg were really rather spartan. Not to mention cramped!

There’s much more in this handsome new museum, however. The development of lighter-than-air flight is documented from the first days of French hot-air balloons.

The fact that Graf Zeppelin achieved pre-eminence in later permutations of this French invention, it’s suggested, was one reason the original museum was gutted of its collections by the French.

This past summer, those old wounds were officially healed. Peace was sealed with a special exhibition and catalogue: “Scenes of a Hate-Love—Zeppelin and France.”

Count Zeppelin, born in 1838, was truly a visionary. Especially as so many of his pilot-models and commercial airships cracked up and crashed over the long years of experiment and development.

In the museum-shop, an excellent and richly illustrated book on the Zeppelins—recently on sale at Barnes & Noble bookshops in an English version—shows that a number of ambitious American army and navy airships also crashed.

Zeppelin was fortunate that some leading German scientists and industrialists were strong supporters, despite the frequent failures. Indeed, Dornier, Maybach, and other aircraft industries grew out of beginnings in providing Zeppelin technologies.

In the midst of World War I, Graf Zeppelin died, in 1917. So he did not witness Germany’s crushing defeat. Nor the French seizure of his dirigibles.

What he might have thought about the tremendous financial—and propaganda—investment of the Nazis in the Zeppelin Industry after 1933 is an interesting subject for speculation.

In any event, Zeppelins with huge black Swastikas—on the white ground and red field—were often seen over Europe’s great cities. As well as over major centers on Zeppelin world cruises.

Among the ribbons, trophies, photographs, and documents in the museum’s exhibition cases are a number of items bearing the Nazi Swastika. The Zeppelin History has not been sanitized for modern viewers.

Nor is Zeppelin out of business. The great factory-complex still stands on the fringes of Friedrichshafen.

But now the firm has diversified into heavy equipment. Great Zeppelin construction-cranes are now seen all over Germany. And notably in Berlin, where a frenzy of new construction is taking place.

Above the harbor, today teeming with tourist-ships from Lindau, Bregenz, and other cities ringing the southern end of the Bodensee—there stands a great pillar. This is the city’s memorial to Graf Zeppelin, surely its most famous citizen.

The Zeppelin Museum also contains Friedrichhafen’s considerable collection of Medieval and Baroque artworks. These evidences of its historic past contrast handsomely with the evidences of its recent Zeppelin Past, as well as with exhibits of present technology and future planning.

There’s also a nearby School-Museum. It documents the development of schools from monastery-schools around 800 AD to the present. Artifacts and information are crammed into nearly 20 rooms. Actual classrooms from 1850, 1900, and 1930 have been reconstructed.

Homesick tourists from the American Southwest may also want to visit Friedrichshafen’s Kakteensammlung. On view in the City Gardens are some 800 species of cactus!

And on the neighboring island of Mainau, you can also see California Redwoods and Mediterranean flora. These trees, plants, and flowers cannot thrive in the harsh winters of the mainland. That they prosper on an island in the middle of Lake Constance is something of a mystery.

Bayreuth’s Bibiena Opera-House Is 250!

| |

The other is the Bibiena-designed Opera-House in Bayreuth, constructed at the command of the Margravine Wilhelmine, Frederick’s favorite sister.

Of course the sisters’ powerful and autocratic brother had his own private opera-house. The stately Court Theatre of Friedrich der Grosser, in his Potsdam Palace of Sans Souci, is smaller than either of his sisters’ playhouses and much more severe in its decor.

But, like the Drottningholm, Wilhelmine’s Bayreuth Court Theatre only seems to be decorated with the most costly of materials. Its elaborate marble pillars and panels, its gilded baroque swirls, are all painted-plaster artifice, laid lavishly over humble wood and stone.

This year is its 250th anniversary. And it is still a popular performance venue, featuring a week-long season of 18th century operas and many concerts during the year.

This theatre, in fact, is the reason Richard Wagner chose Bayreuth for his Festival. He soon realized, however, that its mechanical stage would not serve his innovative visions of opera-production. And that its lovely “Golden Horseshoe” galleries would not accommodate the crowds he rightly anticipated.

Sound & Light Recreate a Golden Age

From April until the end of September, both the theatre and the Neues Schloss [New Palace] of the Margrave and Margravine of Bayreuth are sites of a remarkable exhibition: “The Forgotten Paradise—Galli Bibiena and the Court of the Muses of Wilhelmine.”With artworks borrowed from as far afield as New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, the amazing flowering of culture in this small, isolated provincial city is chronicled. With Wilhelmine’s Court Theatre as its centerpiece.

Even after September, visitors to Bayreuth will be able to tour this elegant playhouse. But it has been made even more interesting with the Sound & Light show devised for the anniversary celebrations.

As the simulated candlelight in the glittering auditorium dies down, details of the richly ornamented theatre are highlighted as its story—and that of Margravine Wilhelmine—is told in images, spoken dialogues, and music.

The theatre was designed by Giuseppi Galli Bibiena, aided by his gifted son Carlo. So prolific were the Bibienas that their theatres and scenic decors were to be found in major cultural centers in the 18th century.

In the Neues Schloss, engravings and models illustrating the achievements of a number of talents in the Bibiena Family are on display. They were able to achieve the effect of monumental architecture on rather small stages.

This they did with what was called Scena ad [or per] Angolo. Instead of designing a central upstage perspective vanishing-point—to make scenes seem endlessly extending on rather shallow stages—they devised off-stage vanishing-points.

For audiences, the effect was of even more grand and amazing temples, palaces, and colonnades—architectural constructions which seemed to go on forever—although unseen beyond the stage-right and stage-left borders of the proscenium-arch.

What made these overpowering scenic environments—all rendered in only two dimensions—even more astounding was that a magnificent palace could vanish in a matter of seconds. To be almost instantly replaced with an enormous military camp, the Roman Forum, or the cloudy realms of Paradise.

This was made possible by an ingenious system of drops and wings, all moved simultaneously from under the stage by a great capstan and ropes and pulleys.

This could be done with the curtain down, but audiences loved to see the actual “transformation” from one scene to the next. It is still a thrill to see this in action at the Drottningholm, which has a number of surviving 18th century sets for drama and opera.

Indeed, the Transformation is still one of the highlights of traditional English Pantomimes!

Wilhelmine’s opera-house no longer has this scene-shifting system in place, being used so often and variously for modern performances. But when baroque operas are revived on its stage, the effect of Bibiena scenery is temporarily recreated.

Anniversary Programs Salute Baroque Opera

Margravine Wilhelmine opened her opera-house to honor the State-Marriage of her only daughter, Frederica Sophia, to the Duke of Württemburg. The opera of choice was Johann Adolf Hasse’s “Ezio.”“Ezio” was revived for the anniversary. As were other baroque operas, oratorios, and concerts. Among them—Henry Purcell’s “The Faery Queen,” Georg Friedrich Händel’s “Alexanderfest” [or “The Power of Music”], his oratorio “Susanna,” and Mozart’s “Gärtnerin aus Liebe.”

There was also a production of “Don Giovanni” from Goethe’s summer theatre in Bad Lauchstad. This is another small gem of a playhouse, with all its mechanical scene-shifting in place. But, thanks to some DDR cultural maven, now operated electrically.

And ex-DDR composer Siegfried Matthus had his opera, “Farinelli, or the Power of Singing,” performed by the ensemble of the Hof City Theatre.

Considering the difficulties in recreating Farinelli’s more than three-octave vocal range for the film—some of which was shot in Wilhelmine’s opera-house—it would be very interesting to hear how Matthus has managed this in his score.

Of course no German festivities would be complete without scholarly analysis of their contexts. Among these interesting events were a symposium of “Music and Theatre at the Court of an Enlightened Princess,” “Women’s Life in 18th Century Europe,” and a lecture on stage-designer Carlo Galli Bibiena by Dr. Oswald Georg Bauer.

Dr. Bauer, Secretary of Bavaria’s Akademie der Schönen Kunste in Munich, is an expert on 18th century and 19th century theatres and their decors. He has written admirable books on Richard Wagner and productions of his operas. He was also, for a number of years, Press Chief of the Bayreuth Festival.

Theatre and design-students even contributed an exhibition evoking the world of Baroque Theatre, its designs, and its machines. This was called “Fascination of the Stage—Baroque World-Theatre in Bayreuth.”

Talented teens from the Gymnasium Christian-Ernestinium showed their models and sketches in the banking-halls of the Kreissparkasse Bayreuth-Pegnitz.

The Magnificent Margravine Wilhelmine—

The Prussian Princess of Brandenburg-Bayreuth

Not only was the Margravine’s opera-house feted in the exhibitions and cultural events, but so was she, remarkably talented and intelligent as she was. In the extensive Neues Schloss, the life of the Court of Bayreuth was chronicled and evoked in many of its precious baroque halls, salons, chambers, and nooks. But even when all the added exhibition music, song, spoken texts, documents, artifacts, engravings, paintings, and photos have been removed, the splendidly furnished, ornately gilded rooms of the palace will remain for the steady stream of tourists who flock to Bayreuth even outside Festival Season.

Given the political, social, educational, and cultural repressions restricting women in the 18th century, it’s lucky that the lovely Wilhelmine was born a Prussian Princess. But she made much more of her fortunate opportunities than many another high-born lady. Most became, in effect, “Trophy Wives” for some minor King, Prince, Duke, or Count.

Wilhelmine was, however, a very specially gifted and perceptive woman. In any age, she would have made a mark, even today!

Her sparkling and thoughtful correspondence with Brother Friedrich shows why he loved and admired her so much. As do letters to and from Voltaire, who broke with the Prussian King, but remained a lifelong friend of Wilhelmine.

Not only did she write plays and librettos for her theatre—as well as compose and play music, as did her brother in Potsdam—but she was also an accomplished portrait-painter.

Her ideas for construction and decoration of court residences and garden-layouts suggest she would have been an outstanding interior decorator today.

Even when the 250th anniversary is over, and the exhibitions are no more, visitors to Bayreuth should make a point of touring all the Margräfliches palaces, residences, and retreats. These include the spacious Neues Schloss in the heart of Bayreuth and the extensive park and pavilions of the Eremitage.

This charming Hermitage has formal baroque gardens, fountains, and grottoes—in addition to another “Neues Schloss” and the old Hermitage, for princely meditations. It also has the customary complement of Baroque Classical Ruins, temples, shrines, and statuary.

But there’s also Schloss Sanspareil—with its outdoor stone Ruinentheater—and Schloss Fantasie, where Wilhelmine’s daughter, Frederica Sophia, lived after her marriage to the Duchy of Württemburg soured.

Wilhelmine left her mark on all of these baroque masterpieces. There’s even a Jagdschloss, or Hunting Castle.

The gardens and central canal behind the city castle are rather restrained, compared with those at the Eremitage. But they border on at least two interesting properties, open to the public.

These are Richard Wagner’s Haus Wahnfried, complete with the garden-vault which contains his remains and those of Cosima Wagner. Nearby is a small stone marking the grave of his favorite dog, Rus.

Before the Order of the Eastern Star—

Wilhelmine and Her Mopsas!

Also just off the gardens is Bayreuth’s Museum of Free Masonry. Frederick the Great became a Mason—as did many nobles and intellectuals of the Enlightenment—and inducted his brother-in-law, the Margraf of Bayreuth. Several lodges soon were formed in the city. Not to be outdone, Wilhelmine and some close women friends created the Mopsas. This was a feminine equivalent of the Free Masons. But it wasn’t the same as today’s Order of the Eastern Star.

Period engravings of the Mopsas’ Degree Work show—similar to Masonic ritual inductions—women with hangman’s nooses around their necks and a schematic coffin on the floor, surrounded by candles. This was to facilitate a ritual death and a rebirth into a new life of fellowship.

Friendship and Loyalty were central to the Margravine’s life. She especially prized those qualities in her toy dog, Mopsa, from which her Masonic secret society took its name.

One of her very close woman-friends even carved their initials inside a heart on one of the pillars of the old open-air “Roman” stone-theatre in the gardens of the Hermitage. To this day, you can see this token of love.

What Wilhelmine did not know was that trusted friend was secretly reporting court affairs to the King of France.

Several interesting books have been written about this remarkable princess, but I’ve never seen one in English. There surely must be at least one by now.

Wilhelmine was passionately proud of being a Princess of Prussia. Indeed, the great crowns over the proscenium and the grand loge of her opera-house are those of Prussia.

Her mother had hoped she would marry the heir to the British Throne, but that was not to be.

Her brother wished her instead to marry the Margraf of Bayreuth, the better to secure the loyalty of this Franconian territory. Bayreuth—now part of Bavaria—was quite a distance from Prussia and Berlin.

Wilhelmine, who knew the Austro-Hungarian Empress, Maria-Theresia, was able to steer a clever course between the territorial ambitions of both Prussia and Austria.

But Bayreuth, when Wilhelmine arrived, was essentially a provincial backwater. The Prussian Princess soon changed all that and made it one of Europe’s most cultivated courts!

Taking a [Financial] Bath in Baden-Baden

| |

| Rear Facade of New Baden-Baden Festival Theatre Resembles a Post-Modernist Artwork. copyright © Glenn Loney/The Everett Collection | |

Before the Russian Revolution, Grand Dukes and other Petersburg nobility used to spend part of their summers “taking the waters” at this historic Spa. There is still a Russian Orthodox Church to remind modern tourists of that fact.

The King of Württemburg was especially Russophiliac, so they flocked to his Thermal Springs and Mineral Waters to Take the Cure. Czar Nicholas II even wrote him a long letter about the assassination of a Romanov Grand Duke who was a frequent visitor to the Baden-Baden baths. [This is currently on view at the Morgan Library.]

Empress Augusta and the Kaiser of Germany were also VIPs. Today there are still imposing statues of the Prussian Rulers on the grounds of the Kur-Haus and Casino.

Captains of Industry—including some rich Americans, hungry for titles for their daughters—built handsome villas on the hills and in the vales hugging the ancient town on the edge of the Black Forest.

The Romans were the first to make a thermal healing center here. Remains of their baths have survived.

| |

| This “Bad” Hotel in Baden-Baden Is Good—and Not Only for Deer with Golden Antlers. In German, “Bad” Means Bath—Healthy Thermal Baths! copyright © Glenn Loney/The Everett Collection | |

The glittering Casino is still regarded by experts as one of the most handsome in Europe. It also has its own cabaret shows and other entertainments.

The historic and beautiful Beaux Arts Theatre opened with the premiere performance of Hector Berlioz’ opera, “Béatrice et Bénedick.” It also can claim the premiere of the Brecht/Weill opera “Mahagonny.”

It still produces a regular theatre-season and hosts touring shows. And of course there are open-air concerts for tourists, spa-patients, and the local citizenry.

Visions of Yet Another Summer Festival

Baden-Baden’s former glories—and its small-scale past cultural achievements—recently encouraged some Movers & Shakers to view the spa-city as an ideal spot for a Festspielhaus.Unlike the Grosses Festspielhaus in Salzburg, which is used mainly for a scant five weeks in the late summer, Baden-Baden’s new festival theatre would be programmed year round.

Austrian Salzburg and its world-famous Festival would soon find it had a serious challenger almost on the French border of Germany.

Of course Salzburg is now hardly the only important summer festival of music and opera in Central Europe.

But one of the reasons it became a kind of Negative Touchstone for some of the instigators of the new theatre and festival was their disaffection with the Salzburg Festival.

After the death of longtime Salzburg Festival Artistic Director Herbert von Karajan, some of his closest advisors and supporters found their voices and persons no longer needed by the new director, Gerard Mortier.

They—and a number of Von Karajan’s wealthy admirers—also deplored the disappearance of the Maestro’s lavish opera productions, studded with vocal stars with major recording contracts.

Not only was Mortier determined to mount new productions of cutting-edge virtuosity and innovation. But he was also dedicated to introducing New Music at the Festival—notably to its tradition-bound and very wealthy audiences.

The Von Karajan Survivors—though they could not raise the Master from Hades—thought they could revive the old atmosphere of elegance and splendor of his Salzburg Festival in Baden-Baden.

They wrongly assumed that, if they built the new Festival Theatre, audiences would almost automatically come.

They miscalculated. The handsome new concert and opera-house opened this past April. It is said to be the Third Largest Opera-Stage in Europe!

Only a few days before I arrived to have a look at the theatre, the managing consortium had nearly been forced to declare bankruptcy.

A news-item in an Austrian newspaper noted, the day before my departure for Baden-Baden, that this had been formally averted by the sale of all this group’s rights, options, and liabilities to Baden-Baden for One Deutsche Mark!

Remembrance of Things Past Not Good Marketing!

The Russian Revolution and the Defeat of the German and the Austro-Hungarian Empires in World War I certainly took their toll on the lavish lifestyles of some of Baden-Baden’s most wealthy summer visitors.Nonetheless, between the two World Wars, it continued to attract people with money to lose on the gaming-tables.

It also continued its genteel cultural traditions, with festivals of new music and art exhibitions.

After the Second World War, however—in a divided Europe with severe economic problems both East and West—Baden-Baden was not the magnet for wealthy summer guests it had once been.

As for its merits as a Spa-town—even with the famous spas of Marienbad and Karlsbad inaccessible behind the Iron Curtain—it had a lot of competition.

A brief glance at a map of Germany and Austria will disclose an alarming number of small cities and towns prefixed by the word “Bad.”

That is not a warning, but it is a kind of Travel Advisory. In German, the word means Bath or Baths.

If you travel to Bad Gastein or Bad Tölz, don’t be surprised if you find some steamy springs and bathing facilities.

Konstanze, the jealous Mozart’s flirtatious wife, spent entirely too much time, in his opinion, taking “Cures” in Baden bei Wien. Then there’s Switzerland’s Baden, as well.

The hot and cold mineral waters are supposed to be a real tonic for skin, muscles, and whatever ails you. Along with massage, sound diet, and mud-baths, amazing cures have been claimed.

But, if you boil these waters in your kettle too often, you’d be alarmed to see how the minerals are building up in the bottom. Or eating it away.

Imagine what these mineral-salts might be doing to your stomach!

No matter. People still stream to Baden-Baden.

But they don’t look like the kind of idly rich or ardently cultural who throng Salzburg’s narrow streets during its brief Festival.

Some are clearly low-budget tourists with a gaggle of kids, who have left the van in a parking-lot. Others really look sick.

Baden-Baden’s baths must be on the Approved List for Workers’ Krankenkassen, or Hospital Insurance Plans.

Its central pedestrian streets are often thronged with stooped older people, hobbling along on canes or crutches. Or being pushed along in wheelchairs.

Such sights, however, do not put one in an exuberant festival mood. Quite the contrary. They are depressing.

But this is the frequent daytime scene in Baden-Baden—which, along with its splendid new Festival Theatre, was going to rival Salzburg almost overnight as a premier Festival City.

Abandoned Central Railroad Stations

The special architectural attraction of the new Festival Theatre—designed by Prof. Wilhelm Holzbauer—was to be its siting in and behind the old and still grand Central Station.This was a big selling-point when the project was first broached to the public. The huge and handsome station had not been used for train-traffic for many years.

Tearing it down to be replaced by some modern horror seemed a crime in such an historic city. But turning it into the facade and entrance foyers of a magnificent new Festival Theatre appeared a stroke of genius.

After World War II, a number of German cities—which previously had all their rail-lines terminate in their centers—found the Bundesbahn was relocating stations on the main rail-lines, which were often on the edges of, or even outside, the cities.

Some cities, like Kassel, kept the Central Stations open for local trains and trams. But even Kassel’s monumental station now has multiple uses. Not least as exhibition galleries for art shows such as Dokumenta.

Not only was the closure of Baden-Baden’s Central Station a loss to the life of the city in many ways. But the new main-line station is some three kilometers from the actual city-center.

This means that tourists passing through—especially Americans on Eurail Passes—see nothing of interest that would make them want to stop over and look around.

I must confess that, on a number of occasions, riding a fast train toward Strasbourg or Munich, I considered making a brief visit to see this famous spa. But the station and its non-descript surroundings looked so uninteresting I didn’t bother.

They are still banal and boring.

In fact, the first time I actually saw Baden-Baden was one day this past August. I left Austrian Salzburg very early in the morning and crossed Germany by very fast train.

I must admit I was quite surprised at how beautiful and historic the city is. And how many really elegant hotels it has.

Not to mention the villas and estates of some very Rich and Famous Celebrities. Some of the elegance is faded, but some is bright and fresh.

High-Rollers still come to gamble in the Casino. The riding and Horse-Races are still big attractions.

The fact that there is still Big Money in Baden-Baden—or that it often comes to spend itself during the season—must have unduly encouraged the Festival’s Planners.

They obviously believed they’d have no difficulty in filling their 2,500-seat theatre for a variety of seasonal festivals. Its architect, Prof. Holzbauer, also was skillful in designing it for multiple uses.

But they were wrong. They didn’t do their Performing Arts Management Homework.

An axiom of performing arts management is that Great Oaks Grow From Small Acorns. Few great summer music-theatre festivals in Europe began full-blown, with huge new theatres.

Salzburg’s famed Festival began rather modestly, though the contributions of the dynamic director Max Reinhardt did much to win it initial attention.

The Edinburgh Festival began tentatively with the import of some Glyndebourne opera-productions by Sir Rudolf Bing.

Richard Wagner’s Bayreuth Festival opened in 1876, in a “temporary” theatre which has never been replaced, only renovated. Because of funding problems, it often was held only every other summer. And sometimes, not at all, during Germany’s worst 20th century economic crisis.

The Baden-Baden Festival would have done well to begin more modestly, using existing performance venues and building gradually on the foundations of earlier music festivals in the city.

The planners of the Festival Theatre didn’t really study the demographics. Nor create imaginative advance-advertising and devise the sound marketing strategies necessary to attract large and interested audiences.

Politicians and Planners willed the Festival and its Theatre on Baden-Baden.

Without making any real effort to win the support of the local citizens: crafts-people, office-workers, shop-keepers, laborers, and professionals.

Community Out-Reach with Free Seats!

I came on the frantic backstage scene just as the new Press Chief, Dr. Jacob, was preparing to hold a press-conference.Valery Gergiev and his Kirov Opera and Orchestra would open a week’s engagement only two days hence.

But advance sales had been so disappointing that the new management—representing the City of Baden-Baden’s interests—was offering every seat in the house absolutely free for the Kirov engagement!

All local citizens had to do was write in a request. Anyone who had already paid would get both the tickets and the money previously paid!

This may not seem an effective way to recover from virtual bankruptcy. Or to make enough of a profit to pay off the considerable remaining costs of the new theatre.